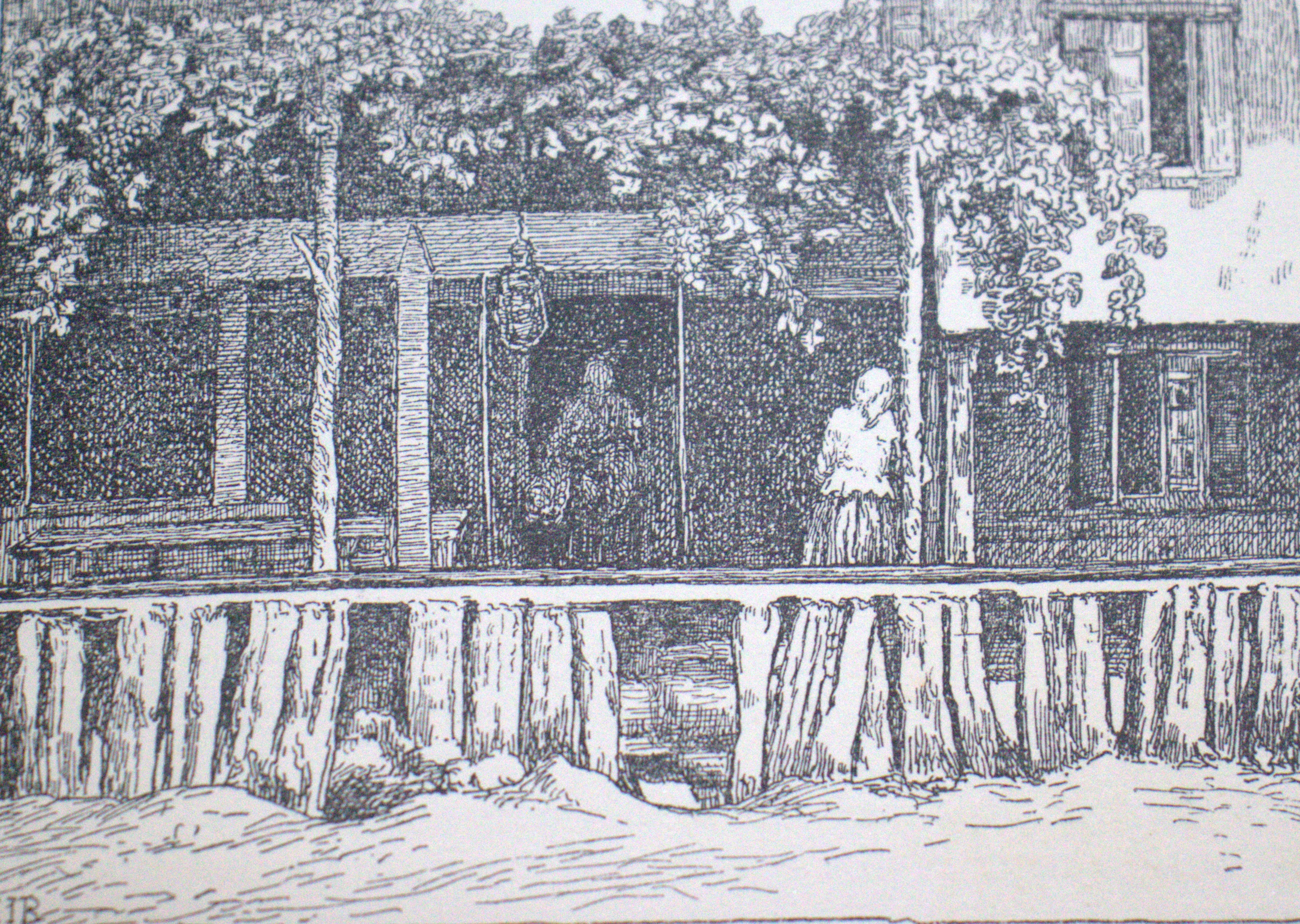

Emilie Isabel Russell Barrington, 'Railway station between Patras and Corinth,' Through Greece and Dalmatia (1912), 39.

As they traveled through the regions that comprise the modern nation of Greece, each of the women carried with them individual perspectives influenced by factors such as gender, race, and economic status. Rather than passive viewers, the women offered to their readers insights on the Greeks’ political circumstances. The women noticed how Ottoman rule, and European cryptocolonialism affected the lives of the people—especially the women—they encountered during their journeys. For many, their journeys were shaped by political events: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu traveled as part of a diplomatic mission, and Emily Ann Smythe was on Corfu when the Treaty of London was signed, a turning point in the reunification of the Ionian Islands with Greece. As foreigners, and women, the travelers were also deeply aware of how their own positionality limited and allowed their travel. The national boundaries they and their companions navigated often differed from those of the modern Hellenic, Balkan, and Middle Eastern states. Despite their often nuanced and progressive views, the women’s travel writing also includes now-outdated perspectives influenced by the Orientalist paradigms of the time.

“The Consul's wife, Madame Gaspari, and I went into a room which precedes the Bath, which room is the place where the women dress and undress… I saw here Turkish and Greek nature, through every degree of concealment, in her primitive state—for the women sitting in the inner room were absolutely so many Eves—and as they came out their flesh looked boiled… I think I never saw so many fat women at once together, nor fat ones so fat as these. There is much art and coquetry in the arrangement of their dress… We had very pressing solicitations to undress and bathe, but such a disgusting sight as this would have put me in an ill humour with my sex in a bath for ages. Few of these women had fair skins or fine forms—hardly any—and Madame Gaspari tells me, that the encomiums and flattery a fine young woman would meet with in these baths, would be astonishing…” — Elizabeth Craven, A Journey Through the Crimea to Constantinople (1789), 341-3

“Here we found the ruined roofless villages of the unfortunate Suliotes dotted along the valley, and mostly reduced to heaps of stones; not a stone had been replaced since 1803, for who is there left to do it?” — Emily Ann Smythe, The Eastern Shores of the Adriatic in 1863: With a Visit to Montenegro (1864), 40

“...leaving Scio (the ancient Chios) on the left, which is the richest and most populous of these islands…the women famous for their beauty, and show their faces as in Christendom. There are many rich families…they enjoy a reasonable liberty, and indulge the genius of their country… Their chains hang light on them, tho’ ’tis not long since they were impos’d not being under the Turk till 1566.” — Mary Wortley Montagu, Turkish Embassy Letters (1763), Vol. 3, 67-8

“The War of Independence is stll green in the memory; it is only ninety four years since the protomartyr Rhigas, poet and patriot, was murdered in prison at Belgrade, and his body thrown into the Danube. The people have not had time to shake themselves free of those years of gloom ; no doubt the rising generation will be lighter of heart. The poems may sing of 'the gay pallikar,' but the life he led, which was little removed from that of the wild beast, had in it no element of gaiety, and it was only through sacrifice, such as this, that the sons of Greece won through to freedom.” — Isabel Armstrong, Two Roving Englishwomen in Greece (1893), 10

“That these unsurpassed sculptures, these maidens of Athens, could be liberated from the prison of a museum, and placed again in the full light and air under the fair sky of Greece, round the temple of their goddess, for whom they were created, facing the setting sun, and viewed across the plain as the ships arrive in the harbour of the Piraeus!” — Emilie Isabel Russell Barrington, Through Greece and Dalmatia (1912), 102-3

“The exclusion of all the female world is absolute: no woman is ever permitted to land on any part of the Holy Mountain [Mount Athos]; nor do they admit cows, hens, or any other specimens of the softer sex. Report says that more than one adventurous lady has attempted to evade this rule by landing from a sailing-boat on an uninhabited part of the coast;” — Mary Adelaide Walker, Through Macedonia to the Albanian Lakes (1864), 22