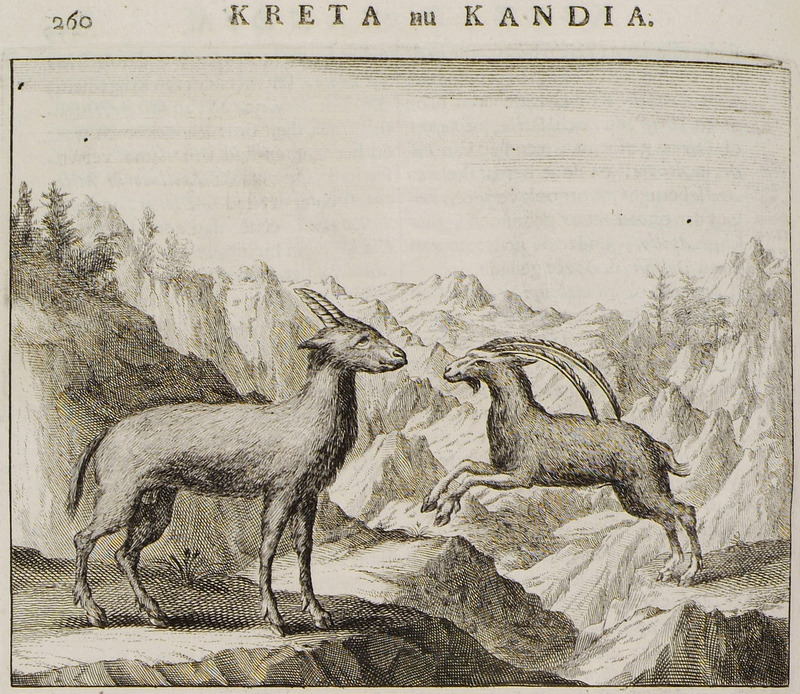

Olfert Dapper (1688), Mouflon (Ovis orientalis) and Cretan kri kri goat (Capra aegagrus creticus). Hellenic Library - Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation.

Women travelers, like their male counterparts, were ardent explorers of science, medicine, and botany during their journey through Greece. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the European scientific community was predominantly a male-dominated intellectual sphere in which women’s voices were often absent from the discourse. Especially notable are the women traveler's ethnographic observations on medical treatments in a world that frequently discounted women's embodied experiences. While faced with resistance from the elite academic community, women travelers were trailblazers determined to engage in the broader scientific and intellectual community. Their travelogues document their interest in the local community and environment, from collecting and classifying fauna and flora to popularizing life-saving medical treatment among the European elite, contributing to the greater scheme of colonial knowledge production. These narratives not only offer a unique perspective on scientific discourses but also attest to their intellectual agency.

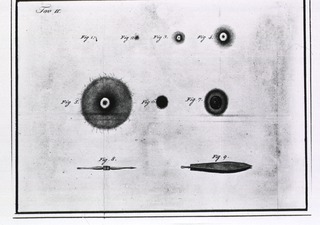

Smallpox: Instruments for inoculation and developing pustule (1801), U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Medicine and Healing

“The small-pox, so fatal and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless, by the invention of engrafting…There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn…the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of matter of the best sort of small-pox and asks what veins you please to have open’d…every year thousands undergo this operation…and you may believe I am well satisfied of the safety of this experiment, since I intend to try it on my dear little son. I am patriot enough to take pains to bring this useful invention into fashion in England and I should not fail to write to some of our Doctors very particularly about it…” — Mary Wortley Montagu, Turkish Embassy Letters (1763), Vol.2, 59-62

“Be provided with medicine in case of fever or diarrhea, as accidental exposure to an evening dew on an empty stomach may bring both.” — Emily Ann Smythe, The Eastern Shores of the Adriatic in 1863: With a Visit to Montenegro (1864), 61

“One group of buildings, surrounded by trees at a short distance from the road, appeared in good repair and inhabited; it proved to be the chapel and holy spring of St. Anthony. Georghi says that many sick people go there, and after a short stay return to their homes cured; feeling, as I do at the moment, the pure health-laden breezes that are sweeping across the plateau, I think this result highly probable, but Georghi prefers to think it miraculous.” — Mary Adelaide Walker, Old Tracks and New Landmarks (1897), 214

![]()

Iconographia Zoologica, UBA274. Allard Pierson.

Wild Life

“Bustard: come in during the winter; their stay is uncertain. They are magnificent birds; I have shot one weighing thirty-eight pounds” [presumably referring to a Great Bustard (Otis tarda)]. — Emily Ann Smythe, The Eastern Shores of the Adriatic in 1863: With a Visit to Montenegro (1864), 63

“Every branch in this garden, under my windows, seemed alive with “cicadas;” their shrill, piercing, persistent chirrup is at first very painful to the ears, but this effect soon passes off. It is always with pleasure that I hear it now, as it never fails to bring back to me the cloudless skies and brilliant sunlight of Macedonia.” — Mary Adelaide Walker, Through Macedonia to the Albanian Lakes (1864), 36-7

“One of the gentlemen in the first carriage had a mania for collecting, and his fancy had gone out to-day in the direction of green tortoises. As we drove across the prairie in the morning these beautiful coloured creatures were out basking in the sun, and every ten minutes a halt was cried, whilst the driver, grinning from ear to ear at the extraordinary craze of this foreigner, was sent back to pick up another specimen, and by the time the Vale of Tempe was reached he had the carriage full of them.” — Isabel Armstrong, Two Roving Englishwomen in Greece (1893), 198

"Sage-Salvia". J.P. de Tournefort 1717. Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation Library.

Botany

“A peculiar kind of sage grows in these parts, called by a French writer sauge à pomme; the natives drink an infusion of the leaves ; it has a stronger scent and flavour than our sage tea, and is accredited with great medicinal virtue. My young Cretan at once stuck a large sprig of it behind his ear.” — Mary Adelaide Walker, Old Tracks and New Landmarks (1897), 221

“The characteristics of the country on this day's journey were totally different to those of yesterday… the very flowers had changed their nature. Yesterday there were anemones of every shade of red and pink, tall, white stars of Bethlehem, vetches of different size and colour, iris, asphodels, and quantities of other flowers; but to-day small hardy little blue anemones, with an occasional white one, took the place of the gorgeous red tribe, the yellow star of Bethlehem stood against the wind, whilst its white sister barely showed her stars above ground, scentless violets on long stalks lifted their heads above dead leaves, and a little purple pink flower kept close to the earth.” — Isabel Armstrong, Two Roving Englishwomen in Greece (1893), 60

“The only pretty shrub to be found on the islands is the rose-laurel, which is now covered with the flower, but the Greeks imagine it diffuses a noxious vapour, and avoid touching or going near it. I found out one thing which may be of use to soldiers or sailors—We had endeavoured in vain to get fruit or garden-stuff—a prodigious quantity of large thistles was the only thing that presented itself—I desired the largest heads might be picked, and had them boiled, which, without being partial, I can assure you, were infinitely better than artichokes—but they must be dressed immediately, for if they are kept till the next day they become so hard that twelve hours boiling will not make them tender.” — Elizabeth Craven, A Journey Through the Crimea to Constantinople (1789), 270

“Soon after we trotted down into a wide glade, shaded by magnificent trees, which opened out into a broad valley, with long lush grass. Here, before a hut built in the arm of a tree, we halted, and the nine hot horses made for that grass… On the other side of the bridge, hanging over the river, there was a beautiful specimen of the sweet-scented flowering willow, and with a little difficulty some lovely bunches were gathered, but not one of all those Greeks knew the name of it.” — Isabel Armstrong, Two Roving Englishwomen in Greece (1893), 192-3

“We cross streams, and the wild rhodedaphnea (oleander) holds rosy sunsets of its own, glowing blossoms tossed up from out the shaded water-beds.” — Emilie Isabel Russell Barrington, Through Greece and Dalmatia (1912), 124